The Story of Harry Constable Podcasts

Listen to a series of podcasts telling the story of Harry Constable read by Christopher Eccleston and Eithne Browne, and based on recordings compiled by Bill Hunter.

Harry Constable - In his own words

Published by Living History Library May 2017

“Every docker filled with pride,

when they had Harry by their side.

In London or in Merseyside,

no honour could be greater.”

From the song: ‘If Harry Don't Go' by Alun Parry

Introduction by Bill Hunter

A great proportion of the British working class emerged from the Second World War determined that they would not allow a “return to the ‘thirties,’ with the poverty and unemployment that this phrase conjured up. In the first two and a half decades after the end of this war, there was a stormy period of strikes and struggles.

There was a desire for big advances in wages and conditions of living and work; an anti-capitalist feeling that was expressed politically by the return of a Labour Government. In mining, engineering and transport, a complacent and settled bureaucracy in the unions attempted to block struggle, and the discontent erupted in rank and file unofficial action.

Dockers were in the forefront of some extremely important struggles of this rank and file movement. These memoirs contain the recollections of a leading participant in the dockers’ struggles of that period. Harry Constable was one of the most outstanding, talented leaders in the unofficial movements that became a most important feature of union history in these years. He became known, and respected among workers in all the major docks in Britain.

A man of tremendous ability

In its issue of 11 December 1975, an east London paper - The Port - had a long article on Harry Constable. The Port was published fortnightly as an ‘independent port newspaper’ with news on all aspects of dockland and was read widely in the east-end of London. The paper began by quoting John Cavanagh, who was at that time chairman of the tally clerks' Joint Advisory Committee in the Transport and General Workers Union, who declared: “He was a man of tremendous ability. He was so eloquent and able to think in depth on all industrial problems.”

Harry’s father and grandfather were dockers. He was brought up in Wapping and had sixteen brothers and sisters, several of whom perished in the poverty and hardship of the dockland area before they reached their teens. His mother was an Irish republican and Harry knew a large number of Irish revolutionary songs and poems.

He had an ability to train a leadership around him which no other unofficial leader ever equalled. He had a national reputation, as a principled fighter -with particular support in Merseyside and London.

In the 1940s and 1950s, when the docks unofficial movement was growing, Constable and the young leaders he gathered around him, kept in touch by travelling to ports to make personal contact, and also by continuous correspondence.

He describes in these memoirs, the events which led to him and two other unofficial leaders being expelled from the Transport and General Workers Union and how he was defended by the rank and file with great demonstrations and strikes. The feelings of rank and file dockers ensured that he continued to be hired by dock employers.

In They Knew Why They Fought – I gave some details about the reaction of the dockers, which forced the employers to give him work. What I wrote then adds to what appears in his memoirs.

The dockers in the control where he attended for hire, decided that when the employers called them out for work, they would refuse to go until he was given a job. They picked a time when trade was brisk in the port. I was told that the action was taking place, was smuggled into the control and it was one of the great experiences of my life.

Docker after docker was called for hire, and replied with a shout: “If Harry don’t go I don’t go.” West India Docks were eventually at a standstill.

Eventually, the employers asked for negotiations and Constable was asked if he would participate in talks with the employers. However, he stated conditions: union officials could be present, but they were to say nothing while he put his case - and that of other men - who in the dockers’ opinion, were being victimised. The employers agreed.

Harry not only negotiated a guarantee that there should be no victimisation of himself, but also that old dockers would be found jobs.

The union officials then hurried out of the meeting to tell the strikers, and urge them to return to work as Constable had made an agreement. The strikers refused to believe them and said they wanted to hear it from Harry Constable himself.

Harry arrived and reported to them. Result: the men still refused to move and passed a resolution that he should have the pick of the jobs at hiring. The employers had to agree.

The sequel came at the hiring. Constable was informed of the best jobs going. He then asked: “where is the worst?” He was told where that was, and said: “Right! I’ll have that,” and was given a resounding cheer from his fellow workers, as someone who would not use their sacrifice to get a privileged position. Soon after this Constable joined the NASD, the blue union.”(They Knew Why They Fought.)

Harry Constable was deeply attached to the east-end of London and to the history and life of the common people who inhabited it. His memoirs recollect his growing up in the east-end of London and his experiences in the army.

In 1950 he was arrested together with another six unofficial leaders and charged under wartime regulation 1305 which curbed the right to strike. Dockers in most ports stopped work several times during the trial at the Old Bailey and demonstrated out side the court.

This Old Bailey case became a landmark in working class history and when the dockers were acquitted, the labour Government withdrew 1305.

Harry was forced to retire from the docks at the end of the 1950s, owing to a legacy of injuries he suffered during the war when he worked as a sapper in the army and on bomb disposal.

Taping his life

I first met Harry soon after the war. At that time he was a member of the Communist Party. He later became a member of the Trotskyist group in the Labour Party and wrote for the paper Socialist Outlook.

Harry died in December 2000. He ended as he lived, with dignity and courage, effectively living on in the consciousness of many other people.

In 1997, I suggested to Harry that he put on tape his recollections of his life, and particularly his participation in the leadership of struggle on the docks in the decade and a half after the end of the Second World War. I suggested there were a number of questions he could answer and I made regular visits to him collecting tapes, discussing with him, running over transcriptions of tapes and suggesting further questions. Here I must mention the invaluable assistance of two good friends in the transcription of Harry Constable’s tapes into written copy – Dave Finch of Norwood and Keith Sinclair of Hull.

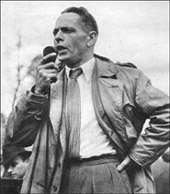

Picture: Harry Constable addressing dockers during their 1950 strike.

Click on the above picture to hear Harry talk about a special day in his childhood.

Harry Constable - In his own words can be found in the following bookshops:

News from Nowhere, 96 Bold Street, Liverpool L1 4HY

Newham Books, 745-747 Barking Road, London E13 9ER

Brick Lane Bookshop, 166 Brick Lane, London, E1 6RU

Housmans Bookshop, 5 Caledonian Road, London N1 9DX

or contact Living History Library: sammydat@gmail.com